Cornwall has been inhabited for thousands of years, since the Palaeolithic or Stone Age. Early hunter gatherers found a diversity of sea creatures on Cornwall’s shores and in its shallow waters. Fish and shellfish have been important foods for people in Cornwall since the peninsula was first inhabited, and are still hugely important today.

Pilchards (Sardines)

Fishing has always been vital to the survival of the Cornish. The oldest, large scale, well documented fishery in Cornwall is the Pilchard fishery. Pilchards have been renamed as Cornish sardines in recent years, but they are the same fish; small, tasty and high in omega 3 oils.

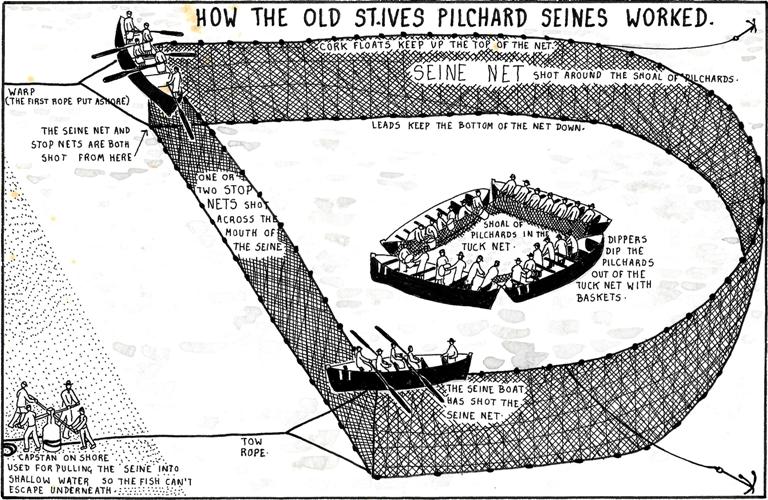

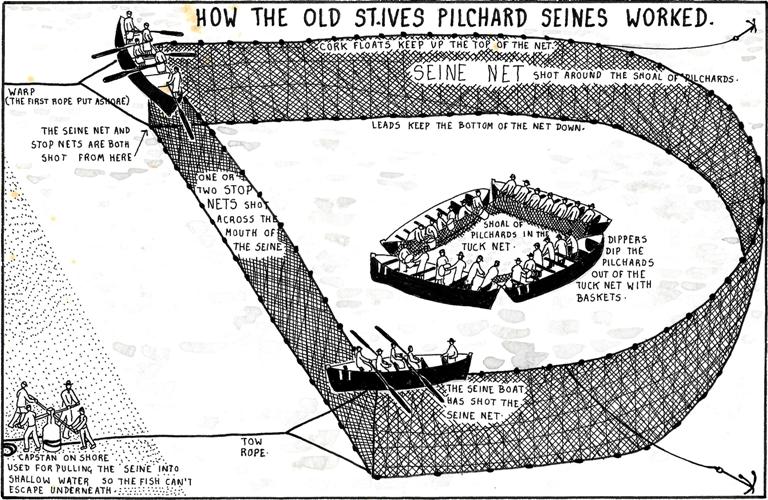

Pilchard fishing using seine nets was carried out all around the coastline of Cornwall. The seine nets used were large and very expensive so they were usually owned by wealthy noblemen, some of whom owned many such nets. Productive bays such as St Ives Bay were home to several seine net operators. Each had their own section of the foreshore and bay in which they had a 'stem' - the rights to fish. The fishery relied on late summer and autumn shoals of pilchard that move north into Cornish waters following warm currents and planktonic food. The shoals were so large that they could be seen from the cliff tops. Watchers called ’huers’ were employed to keep a lookout for the return of the shoals. On Newquay’s Towan Headland a huers hut still stands, originally thought to have been built in the 14th Century.

When the huers spotted pilchards coming into the bays they would call ‘Hevva!’ and wave white spheres called bushes (originally gorse bushes were used) to signal to the teams of men and women in the villages to jump into action.

Image courtesy of John McWilliams ©

Pilchard seines were huge cotton nets with a small mesh and these were deployed in a horseshoe shape like a wall of net around a shoal of pilchards; in a similar way to the method employed by todays beach seiners who fish for bass and mullet. The footrope of the net was weighted to keep it on the seabed and the headrope had cork floats to keep it floating. A traditional seine net could only be used in shallow water, near to shore, and only over sandy or flat seabeds. Heavily constructed double-ended seine boats were used to deploy the net. These boats were up to 40 feet in length and rowed by four oarsmen and a cox. Once the net was set, a smaller wall of net called a 'stop net' was set across the mouth of the seine net. The shoal was now trapped in shallow water. Shore based capstans would haul on the end rope of the seine net to draw it in until the fish were more tightly concentrated within the net. A team of people using four seine boats would then move into the centre of the seine net and deploy a smaller seine, called a tuck net, with ropes attached to the foot rope. Fish were driven into the tuck net which was then held between all four boats and pulled in bringing the pilchards close enough to the surface to scoop them out using baskets.

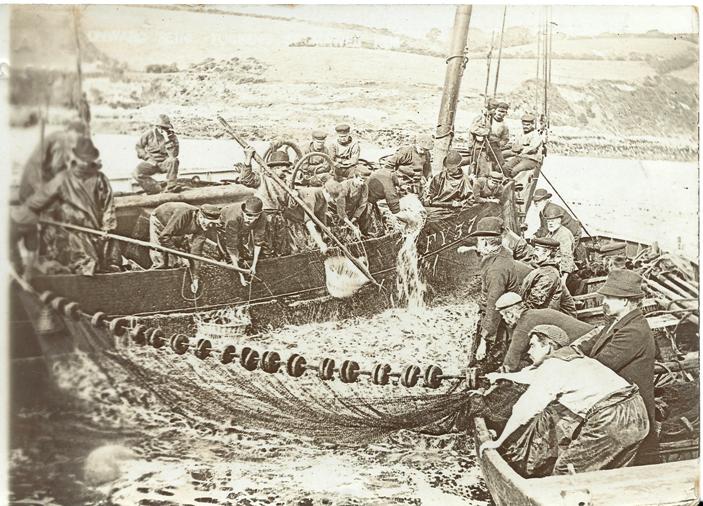

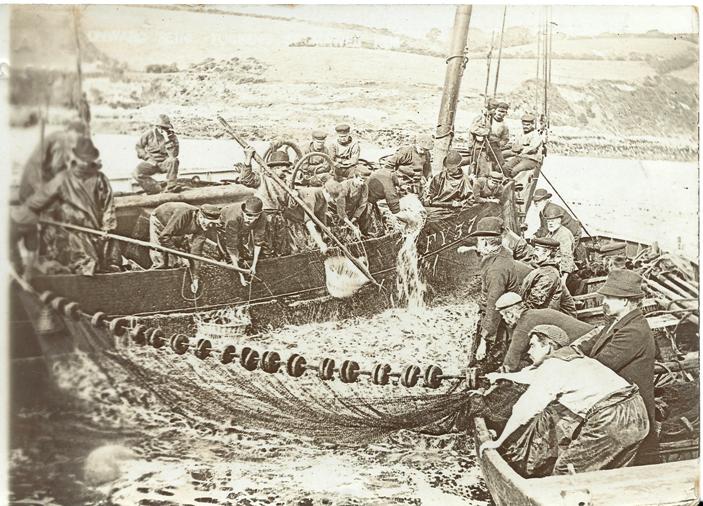

Tucking a Pilchard Seine. Image courtesy of John McWilliams ©

The whole process of seine netting for pilchards was labour intensive and employed huge numbers of fishers, boys and women. The pilchards were processed in pilchard cellars where they were pressed (to remove valuable fish oil), salted and packed into barrels for storage or export. This method of fishing was the main-stay of Cornish fishing communities, and salted pilchards were exported as far afield as Rome where they are still considered a delicacy.

Seine nets were successfully used in this way for hundreds of years but by the late 1890's the fishery had begun to decline. Huge seine nets were expensive, so if fishers wanted to work for themselves, they would use smaller drift nets. These nets were long rectangular nets shot in fleets of several joined together creating a net curtain in the water. The nets were shot at dusk and would drift with the tides, with the fishing boat attached to one end of the row. By the sixteenth century drifters were fishing using sailing boats from most of Cornwall’s harbours.

Mevagissey Luggers heading out to sea to drive for pilchards, c.1907. Photographer S. Dalby-Smith.

Eventually pilchard drift netting or driving became the mainstay of pilchard fishing and the practice of seine netting for pilchards eventually died out. The seiners would argue that the drifters had driven them away from the bays, but for many years the two methods co-existed.

A famous story is told from 1896 when the Lowestoft drifters (from Suffolk) clashed with Mounts Bay fleet. The Cornish were horrified that the East Coast fleet were fishing on the Sabbath, and a group of Newlyn fishers rowed out and destroyed the catch of the Lowestoft boats. Fishers from all across Cornwall got involved and it ended with the army being called in.

During the First World War pilchard drifters began to install motors which made fishing much more practical, and safer than relying on wind alone. You can watch a documentary from 1943 about pilchard drift netting and life in Mousehole during the Great War era at

http://film.britishcouncil.org/coastal-village

During the 1920s and 30s the fleet over-supplied markets and consequently prices fell. At the same time there was competition from canneries in British Columbia who were also flooding the market. The peak of the pilchard fishery was in the 1920s, and by the 1960s the fishery was fading away. This was mainly due to marketing as there was so much competition from overseas. Mid-water trawling for pilchards took off in the 1970s with some boats landing very large quantities, but these quantities were too large for facilities on the shore to handle. Pilchard fishing stopped in the 70s, and remained closed until the 1990s when Cadgwith skipper Martin Ellis began experimenting with ring netting for pilchards. Several others followed suit, and now we once again have a thriving industry based around pilchards - or as they have been re-branded -

Cornish sardines, caught occasionally using

drift nets but more commonly using a

ring net - deployed from purpose built under 10m vessels. There are now aproximately 13 such vessels operating from Cornish harbours.

Herring fishing off Cornwall’s north coast

Herring were traditionally a very important species for Cornish drift netters. Herring were caught during autumn and winter, and from the 1890s until the 1930s herring was the most important fishery on the North coast. Herring were caught in

drift nets and were landed in huge quantities to be salted and sent to markets by rail. They were also smoked and turned into Cornish kippers, and smoke houses were set up in both St Ives and Padstow to process the catch.

Herring nets were similar to pilchard nets but a bit deeper as their mesh sizes were larger. The herring industry was particularly important during the First World War, when larger vessels were called up for service and the smaller Cornish drifters were vital to feed the nation. At this time the majority of the fleet became motorised thanks to financial help from the government.

Sadly these bumper years of herring fishing came to an end during the 1930s, soon after Boulogne steam trawlers trawled over The Smalls spawning grounds (off the Pembrokeshire coast in West Wales). This had a huge impact on the North Cornish herring fishery as herring spawn lies on the seabed and is very vulnerable to damage from trawling (as has been shown in many other areas since). By the 1940's the herring fishery on the North coast had died out completely. Some of the St Ives vessels still fished off Plymouth, but that too had ceased to be viable fishery. Cornish fishers blamed trawlers fishing in Bigbury Bay where the herring spawned.

Herring had made a comeback but stocks of herring in the Celtic Sea are now thought to be at unsustainable levels once again. The Trevose Box closure may help herring during spawning, although a recent report by CEFAS was unable to find evidence of herring spawning in Cornish waters yet. It does however say that herring will recolonise spawning areas once their stocks start to recover. Fishers working just over the border from Clovelly, Devon have started drift netting for herring sucessfully.

Mackerel fishing in Cornwall

Mackerel have been caught by the Cornish for hundreds of years. According to Cornish historians mackerel drifting was introduced to St. Ives by Breton fishermen. Using the same method as the pilchard drivers, the Cornish fished for mackerel with drift nets from lug rigged sail boats. This continued until the introduction of steam drifters in the early 1900s, and eventually motors in the 1920s. The Cornish boats were slow to adopt these techniques, and steam powered drifters built in East Anglia dominated the fishery from 1900 and put many sail-powered Cornish fishing crews out of business. In the 1905 spring mackerel season there were still over 500 sailing drifters working, but many steam drifters had already joined them. A few years later there were no sailing luggers.

Mackerel fishing reached its peak in the 1970s when a so called ‘mackerel bonanza’ saw

handliners making a great living from abundant winter shoals of mackerel along the south coast of Cornwall. This wasn’t kept a secret for long. In 1976 the first large purse seine netters arrived from Scotland and began fishing for mackerel in industrial fashion. Mid-water

pair trawling also started on a huge scale by visiting Scottish vessels. Many of these vessels were landing direct to Russian, Polish, Romanian, Bulgarian and Dutch freezer trawlers, known as factory ships, which could be seen working all along Cornwall’s south coast. This boom created employment for many local fishermen, but devastated local mackerel stocks. When landings were too large for the demand prices fell and huge quantities of good fish were ‘slipped’ - thrown overboard and left to rot on the seabed. In the 1970s ICES fishery scientists estimated that the stock of mackerel in the North East Atlantic was over 30 million. By 1995 the stock was estimated at just 2 million.

Hull freezer trawler 'Arctic Freebooter H362' alongside a Russian factory ship at Falmouth. Photo by Glyn Richards ©.

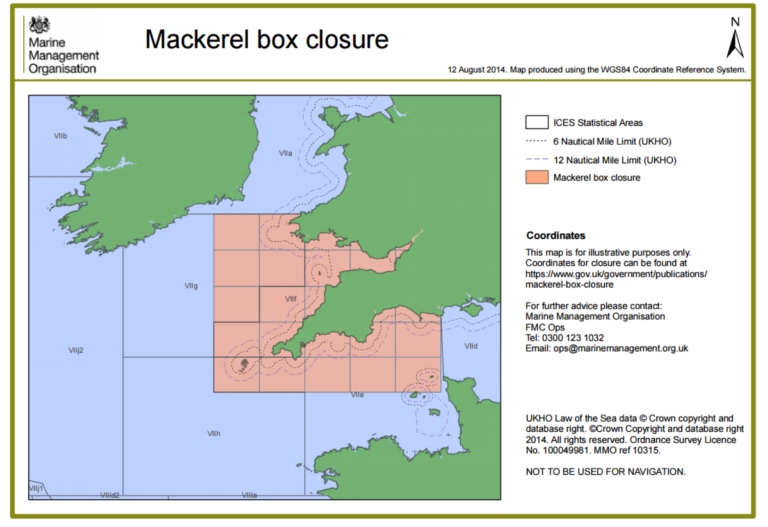

In the mid-eighties the Cornish fishery collapsed. Some thought that shoals may have moved, but all agreed that the fishing effort in our waters had been too high. In 1989 the European Economic Community introduced the ‘Mackerel Box’ an area of 6,7000km2 in which there is a ban on targeted fishing for mackerel by trawlers and purse seiners, and where a hand-line fishery operates with a separate quota allocation. This permanent closure was a successful and long-lasting restriction that has resulted in greatly improved stocks of mackerel around Cornish coasts today. Stocks of mackerel are now estimated to be over 4.6million tonnes in the North East Atlantic according to ICES.

Handlining for mackerel, a traditional low impact method of fishing, has thus become the main method of fishing for mackerel in Cornish waters. This low cost method has enabled small scale fishing operations to continue around our coasts and produces a high quality and sustainable source of mackerel to this day.

Trawling in Cornwall

Trawling in Cornwall was traditionally carried out by sailing boats pulling beam trawls. Sailing trawlers were relatively inefficient, and this was a dangerous occupation that could only be carried out in areas known to be free from rocks and wreckage. Without modern navigation systems and left to the mercy of the elements, sail powered trawling was extremely difficult. If nets were snagged on the seabed the boat could be pulled over and swamped. The majority of trawlers fishing Cornish waters in the early days (c1900) were boats from Brixham, Lowestoft and Ramsgate. By 1910 a total of 138 sailing smacks including 2 steam trawlers were fishing from Cornish harbours, yet none of them were Cornish owned. Longliners disliked trawlers as they often went over their gear and broke their lines.

Trawling smack 'Godrevy LT 475', built at Rye for TA Pawlyn of Mevagissey. Tony Pawlyn ©

The advent of steam engines meant that trawling became far more efficient and with time its popularity grew. The impact on the seabed of beam trawlers in those early days must have been significant, and in areas where herring spawned (on the seabed) damage to the eggs caused by trawling was thought to have been responsible for the collapse of some UK herring stocks.

In the 1930s modern Belgian trawlers equipped with diesel engines began fishing around Cornwall and landing large quantities of fish to Newlyn harbour.

Beam trawlers owned by W. Stevenson and son, Newlyn Photo by Laurence Hartwell ©

The Stevenson family of Newlyn then started buying large vessels, and modifying them for trawling activity. In the late 1960s the Sevenson’s boats were the first in Cornwall to adopt the Dutch design of twin rig

beam trawling. These were found to be extremely effective off the Cornish Coast and Western Approaches. Chain matting at the mouth of the net prevented large stones from being caught. This was highly successful, and by the late 1980s a large fleet operated from Newlyn harbour. This fleet has much reduced over the years due to EU-funded decommissioning and now operates at a relatively low level using vessels that are far smaller than the trawlers found in many other parts of Europe.

Demersal trawling also modernised during this time and many vessels now use this method of fishing. Twin rig demersal trawling is a relatively recent development first utilised by the Danish in the 1980s. This method has been shown to be far more efficient than pulling a single larger trawl. In Cornwall twin rig demersal trawling was developed by the Stevens family of St Ives and their vessel the Crystal Sea, and also by skipper Gary Leach of the Wayfarer SS252 - who pioneered twin rigging for prawns on The Smalls fishing grounds.

Longlining and netting

Longlining is a method that was used for centuries from Cornish fishing ports. The use of baited hooks deployed on long lines and left to fish, allowed people to work despite the weather. This proved to be a very efficient method of catching larger species such as turbot, ling, hake and skate.

The introduction of relatively cheap and durable nylon monofilament gill nets in the 1970s was a much more efficient method of catching large demersal species that live on or near the seabed. This meant that longlining in Cornwall eventually became a thing of the past. Boats were modified to make gill netting their primary method of fishing. Today gill netting boats often have a covered working area so that they can haul nets and fish even in terrible sea conditions. Modern hydraulic net haulers and automatic net cleaners have meant that the amount of net that can be used has increased massively. An average gill net vessel can now set and haul several kilometers of nets per day. The most common type of gill nets used by cornish fishing boats are so called tangle nets - bottom set gill nets that have a large mesh size and are set loose so that passing fish are entangled rather than enmeshed. Gill netting has less impact on the marine environment than mobile fishing gear but the nets can be very efficient at catching fish and there are issues with unwanted by catch of cetaceans, seals sharks and rays. Read our page on gill netting for more information.

Nets are used all around Cornwall’s coasts and are used to catch many different species. Offshore they are used to catch monkfish, hake, ling, rays and crabs, and closer to shore they are used to catch bass, sole, red mullet, brown crab and spider crab.

Potting in Cornwall

Potting for

crab,

lobster and

crawfish was very different in the early days when people used traditional inkwell style pots made from willow withies. The skill needed to be a potter was considerable. Many of the withies used had to be brought down from Somerset, and the creation of pots was a real art form. There are still a couple of people today who can make traditional withy pots, but the art is dying out.

Fisherman making withy pots at Porthgwarra, from an old postcard. John McWilliams

The use of steel, plastic and nylon netting meant that this fishing method became out dated and now crabbing is very different. Pots are larger and heavier, and the use of hydraulic pot haulers means that each boat can deploy and haul far more pots per day than they could before. The fishing method, however, is still just as sustainable as undersized shellfish are returned unharmed, and the gear has minimal impact on the seabed in Cornish waters. Potting is now the most commonly used method of fishing in Cornish waters. Visit our page on Potting

here.

Scallop Dredging

Scallop dredging is a relatively new fishery. First carried out in the 1960s on Cornwall’s south coast, the technology was developed in Scotland and visiting Manx and Scottish vessels were amongst the first to realise the potential for

scallop fishing in Cornish waters. Many beam trawlers and smaller fishing vessels were converted for scallop dredging. Scallop dredging has been massively profitable for Cornish fishermen and now makes up a large percentage of the total value of the Cornish fishing industry. The risks associated with the impact of toothed scallop dredges on the seabed have led to much restriction on this method of fishingin Cornish waters. Scallop dredging was banned from the Fal and Helford area of special interest, after concerns were raised by conservationists about damage to vulnerable maerl beds and nursery stocks of scallops in the estuary and bay in 2009. Find out more about scallop dredging on our page

here.

Further Reading

For a much more detailed account of the history of the fishing industry in Cornwall, with great stories about the lives of Cornish fishermen we recommend the following publications: